LOS ANGELES (Reuters) – Marlon Brando, one of the most influential actors of his generation, has died, according to media reports on Friday citing his lawyer. He was 80.

A family friend told Fox News that Brando died on Thursday night at 6:20 p.m. (2220 GMT) in a Los Angeles-area hospital after being taken there on Wednesday. The cause of death was not immediately known.

Brando, with his broken nose and rebel nature, established a more naturalistic style of acting and defined American macho for a generation with classic performances in “A Streetcar Named Desire” (1951), “The Wild One” (1953) and “On the Waterfront” (1954).

To many, Brando remained the motorcycle-riding rebel he played in “The Wild One.” Asked what he was rebelling against, Brando replied, “Whaddya got?”

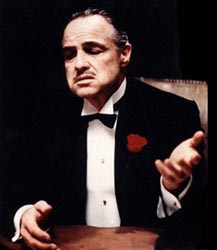

Brando won an Academy Award for “On the Waterfront” and another for his brooding, at times mumbling, portrayal of the patriarch of a Mafia family in “The Godfather” (1972).

But Brando also railed against Hollywood and chafed at the pomp of stardom throughout a stormy career. In 1973, he refused to accept his second Oscar to protest the treatment of American Indians and later professed not to know what had happened to the award. In more recent years, Brando's brilliance as an actor was overshadowed by his eccentric reclusiveness, the turmoil in his family life and financial disputes.

Christian Brando, his son by his first wife, Welsh actress Anna Kashfi, was sentenced to 10 years in prison for the 1990 murder of his half-sister Cheyenne's boyfriend. Cheyenne later committed suicide, in 1995, at the age of 25.

Brando, who was paid a then-staggering $14 million for his walk-on performance in 1978's “Superman,” remained enmeshed in legal disputes over money up until his final weeks.

He poured millions into Tetiaroa, a South Seas atoll he bought in 1966 and where he spent much of the 1980s living out a boyhood fascination with Tahiti rekindled during the shooting of “Mutiny on the Bounty.”

Movies, he said, he made only for the money. “Acting is an empty and useless profession,” he said. Still, Brando inspired a generation of beatniks and rebel actors, including James Dean.

“There was a sense of excitement, of danger in his presence, but perhaps his special appeal was in a kind of simple conceit, the conceit of tough kids,” wrote critic Pauline Kael of the New Yorker.

“Brando represented a contemporary version of the free American,” she wrote.

THE UNIVERSAL ACTOR

Brando was born on April 3, 1924, in Omaha, Nebraska, the son of a calcium carbonate salesman and an actress who coached a local drama group. He was sent to a Minnesota military academy but was soon expelled.

He headed to New York, where his two sisters were studying art and drama. There he took up drama, studying with famed teacher Stella Adler and the Actors' Studio.

“Marlon never really had to learn how to act. He knew,” Adler once said. “Right from the start he was a universal actor. Nothing human was foreign to him.”

In 1946, critics voted Brando Broadway's most promising actor for his role as a returning World War II veteran in the flop “Truckline Cafe.”

Brando broke his nose in backstage horseplay and gained a reputation for being moody. Auditioning for a Noel Coward comedy, Brando tossed the script aside, saying, “Don't you know there are people in the world starving?”

In 1947, playwright Tennessee Williams approved selecting Brando to play the brutish Stanley Kowalski in the stage production of “A Streetcar Named Desire.”

Brando resisted Hollywood until 1950, but then turned in memorable performances in Elia Kazan's 1951 film version of “Streetcar” and “Viva Zapata!” (1952), the story of a Mexican peasant revolutionary.

'I COULD HAVE BEEN SOMEBODY'

In “On the Waterfront,” Brando played a one-time boxer who turns against his friends and brother in a corrupt union.

In one of the most famous scenes in cinema, Brando tells his brother, played by Rod Steiger, “Oh, Charlie, oh, Charlie … you don't understand. I could have had class. I could have been a contender. I could have been somebody, instead of a bum — which is what I am.”

In the 1960s, Brando became active in the civil rights movement, especially for American Indians. He sent Indian actress Sacheen Littlefeather to the Academy Award's platform in 1973 to describe the plight of Indians.

Critics both hailed and panned his performances in “Last Tango in Paris” (1972) and “Apocalypse Now” (1979), but Brando was also legendary for being one of his toughest critics.

“To this day, I can't say what 'Last Tango in Paris' was about,” he wrote in his 1994 autobiography. He also claimed to have talked Francis Ford Coppola into marginalizing his role as the enigmatic Col. Kurtz in order to heighten the mystery.

“What I'd really wanted from the beginning was to find a way to make my part smaller so that I wouldn't have to work as hard,” he said.

In the 1990s, Brando emerged from a decade hiatus to take small roles in minor films, often for outsized fees. He played a Godfather-like mafioso for laughs opposite Matthew Broderick “The Freshman,” and his portrayal of a kindly psychiatrist in 1995's “Don Juan DeMarco,” opposite Johnny Depp, earned him about $3 million in a movie budgeted at $15 million.

Brando was married three times, choosing little-known actresses as his brides — Kashfi, Mexican actress Movita Castenada, and Tahitian Tarita Tariipia, who co-starred with him in “Mutiny on the Bounty.”

“He's full of deep hostilities, longings, feelings of distrust,” director Kazan once said of him, “But his outer front is gentle and nice.”