Right! I know what I’m doing next time I’m in Canada!!!

Earlier this week, the citizens of Sault Ste. Marie, Ont., got their first look at the city’s new coat of arms. It had all the typical elements of a medieval coat of arms, but this was clearly no European design. The motto is in Ojibway, a rugged-looking fur trading post tops the design and the shield is flanked by two timber wolves, both of whom are oddly clutching steelworker’s tools

Canada may have put a leaf on its flag and picked a beaver for its national animal, but along the way it became home to some of the world’s most visually stunning heraldry.

While other countries may stick to lions, unicorns and medieval shields, Canada’s badges and coats of arms abound with bison mermaids, flying polar bears, fire-breathing Chinese dragons and First Nations monsters — all tossed together in whimsical scenes of fire, ice and glory.

And all of it is officially sanctioned by the Queen.

“If people are willing, we’ll be wild, if they want to be conservative we’ll be conservative, but we’re not short of ideas,” said Chief Herald of Canada Claire Boudreau. “I know that what we do is above any standard that I’ve seen internationally. I can say we’re the top; on that I have no question or hesitation.”

For most of Canadian history, any citizen wanting a coat of arms had to go through the rigorous process of appealing to the 500-year-old College of Arms in London. That all changed in 1988 when Canada—at the urging of the country’s heraldic enthusiasts — successfully patriated all heraldry control from the U.K.

Overnight, an art once limited to medieval nobility was within reach of any Canadian with about $2,000 and a sufficiently clean criminal record. In the words of the now 26-year-old Canadian Heraldic Authority, it exists to “ensure that all Canadians who wish to use heraldry will have access to it.”

“If people are willing, we’ll be wild, if they want to be conservative we’ll be conservative, but we’re not short of ideas,” said Ms. Boudreau. Much of this “wildness” comes in the form of consistently odd fauna choices. The Quebec City Ballet features a pair of “half-swan, half-gazelle” hybrids for its coat of arms. The Royal St. John’s Regatta chose a pair of caribou mermaids.

Winnipeger Philip Lee also opted for unusual mermaids; a bison-mermaid on the left and a dragon-mermaid on the right. As an official description reads, the fishtail bottoms of the two creatures are meant to symbolize Mr. Lee’s skills in “water research and limnology studies.”

The Canadian Society of Immigration Consultants chose to feature two winged polar bears. The wings stand for migration, but the ferocious bears stand for “protecting the standards of the immigration profession.”

Even the Federal Court of Canada opted for elaborate monsters: The winged sea caribou, a creature with a caribou head, a salmon tail and raven wings and talons. The fearsome beast represents the court’s involvement in aviation and maritime law.

At Heraldic Authority headquarters just down the street from Rideau Hall, Ms. Boudreau oversees a small staff of “Heralds of Arms” tasked with churning out Canada’s robust annual production of new heraldry. “We’re a young team, we’re totally enthusiastic about what we do, and it shows,” she said.

Half the authority’s applications come from the standard stable of heraldry adopters such as military regiments and universities, but the other half comes from civilians: Normal Canadians simply looking to work with a herald on drawing up a family coat of arms. It is this democratization of Canadian heraldry that often yields its most colourful results.

“We say ‘go for it, mix three animals, we’ll make it beautiful’ — it won’t look weird or tacky, it will just look amazing,” said Ms. Boudreau. “It will be more poetic; you mix a horse with a dove and the result speaks more to you.”

To honour his Chinese heritage and Alberta home, former Alberta Lt. Governor Norman Lim Kwong opted for a pair of half dragon, half Albertosaurus creatures — along with a trio of footballs to denote his 1950s CFL career.

Ms. Boudreau’s own coat of arms features a pair of rainbow-coloured panthers breathing fire. For good measure, the design is topped by a third fire-breathing monster endowed with the “body of a lion, a horse’s head with horns, a griffin’s forelegs and a lion’s hind legs.”

“This diversified nature makes it a symbol of tolerance and of the spirit of adventure by which alone the frontiers of the unknown can be pushed back,” reads the accompanying description.

David B. Appleton with the Royal Heraldry Society of Canada, agreed that the Canadian Heraldic Authority’s “acceptance of unusual fauna … in Canada than is usually seen in the other heraldic authorities.” Probably the most uniquely Canadian heraldic feature is the narwhal, the Arctic whale characterized by its long, spiraling tusk. Although it can be tricky to pose the 100 kg marine mammals into any kind of regal position, several prominent bodies have been unable to resist adopting the creature as a kind of Canadian unicorn.

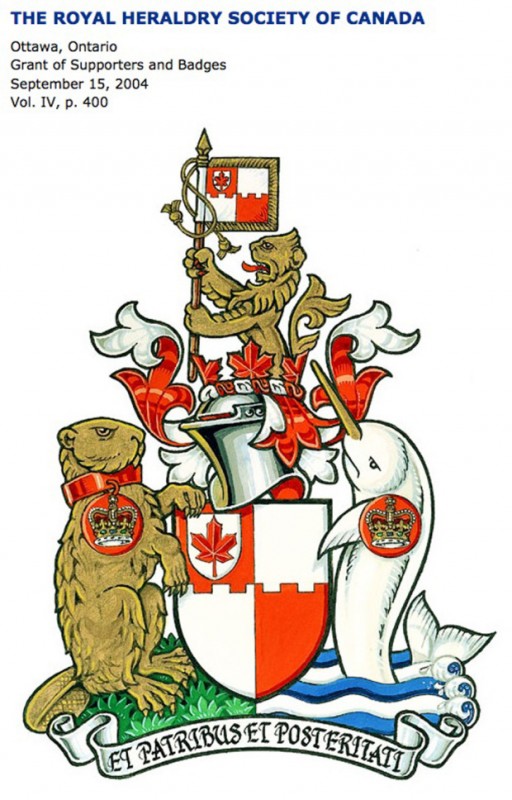

A narwhal balanced on its hind flippers features prominently on the Nunavut coat of arms. The Northwest Territories similarly opted for a pair of demure golden narwhals on top of its heraldic shield and even the Royal Heraldry Society of Canada’s own coat of arms features a stern narwhal paired alongside an equally stern beaver. The Nunavut coat of arms, like many others, also employs echoes of Aboriginal elements — another feature of Canadian heraldry.

Canada “is the only country, as far as I know, which embraces emblems from other cultures,” wrote Royal Heraldry Society of Canada member David M. Cvet in an email to the National Post.

The mottos featured on Canadian coats of arms range from Polish to Hungarian to Inuktitut, and the designs abound with Chinese and First Nations design elements. The Canadian Museum of Civilization, prominently, featured mythical designs influenced by aboriginal artist Norval Morrisseau. Whitehorse, Yukon’s Judy Gingell, meanwhile, obtained a coat of arms in 1998 featuring two Tlingit figures done up in Northwest Coast style.

There are limits, of course. Heralds are bound to maintain some consistency of design — and they have to maintain dignity of the overall heraldic registry.

More than 20 years ago, Major-General Richard Rohmer, one of Canada’s most decorated citizens, when choosing a motto for his coat of arms originally wanted a loose Latin variation of the phrase “always in the s—.” At the urging of heraldic authorities, he eventually downgraded it to the more Quixotic “Ad Proximum Ventum Pistrinum.” Translated: On to the next windmill.