Emphasis, mine.

Historically, lethal injection has been plagued with problems just like those that occurred in Lockett’s case, and they are due in large part to the incompetence of the people charged with administering the deadly drugs. Physicians have mostly left the field of capital punishment; the American Medical Association and other professional groups consider it highly unethical for doctors to assist with executions. As a result, the people willing to do the dirty work aren’t always at the top of their fields, or even specifically trained in the jobs they’re supposed to do. As Dr. Jay Chapman, the Oklahoma coroner who essentially created the modern lethal injection protocol, observed in the New York Times in 2007, “It never occurred to me when we set this up that we’d have complete idiots administering the drugs.” Dr. Jay Chapman said that were he to do it once more, he would not recommend the three-drug concoction now in widespread use.

An injection of chemicals used to execute death row inmates can cause such excruciating pain that veterinarians are banned from using them to put down animals, according to one of the most thorough reviews ever undertaken of the administration of the death penalty.

The report, endorsed by a range of criminal justice experts, urges states have the death penalty to kill an inmate with a single chemical overdose, rather than the “three drug cocktail” used in a series of botched deaths, including Oklahoma’s disturbing execution of Clayton Lockett last week.

Lockett’s attempted execution, which took one hour and 44 minutes from the moment he was first restrained on the gurney, prompted outrage across the world. He was administered a drug cocktail in dosages never before tried in American executions, and complications arose after officials were unable to locate a suitable vein. Witnesses saw him writhing and groaning on the gurney, and it was a full 43 minutes after the drugs were administered before he died.

A spokesman for the United Nations high commissioner for human rights said Lockett’s experience in the death chamber may have constituted “cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment”. President Barack Obama described the case as “deeply troubling” and ordered a review into the wider use of the death penalty by the US Department of Justice, which is hampered by the fact it has no jurisdiction over state-administered executions and still in the process of determining the remit of its inquiry.

The 200-page report published on Wednesday by the Constitution Project, a Washington-based thinktank, carries particular clout because it is endorsed by a bipartisan panel of experts who both oppose and favour the death penalty. They include former judges, police chiefs, attorneys general and governors who have signed execution warrants.

The panel argues that the so-called “three-drug method”, in which death row inmates are administered a drug combination which, by turn induces unconsciousness, causes muscle paralysis and stops an individual’s heart, “poses a risk of avoidable inmate pain and suffering”.

A concern with such cocktails is that if the first, anaesthetising drug fails, as has been known to occur, a patient is at risk of feeling the agonisingly painful effects of the follow-up drugs.

Instead, the report urges states to adopt a “one drug-protocol” that kills an inmate with a single, high dose of an anaesthetic or barbiturate. “The one-drug method is also preferred over the three-drug method by veterinarians for euthanising animals because the one-drug method is more humane and less prone to error,” the report states.

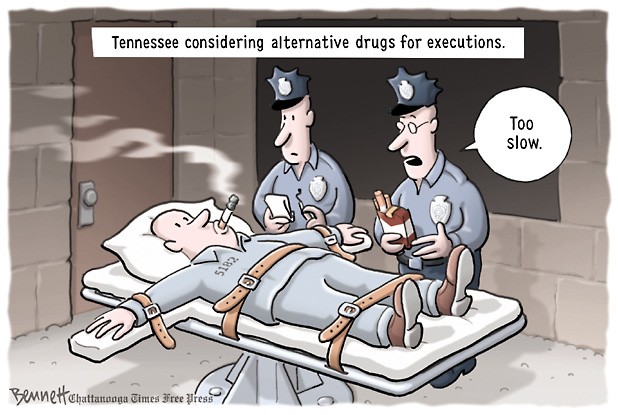

“It is quite true we have executed humans in the United States with drugs that have been prohibited in the euthanising of animals, not just in Tennessee but in a number of states,” said Sarah Turberville, a senior counsel at the Constitution Project.

States have felt vindicated in their use of a three drug cocktail since 2007, when the supreme court ruled that the technique was not unconstitutional. But the Constitution Project’s report argues the ruling is moot, as states have since begun experimenting using different combinations to overcome a Europe-led moratorium on the supply of drugs used in executions.

Arkansas, Georgia, South Dakota, Texas and Tennessee have all passed laws to keep secret their execution recipes in efforts to preserve their relationship with suppliers. “Such secrecy undermines the public’s faith in the integrity of the justice system as it conceals from the public, lawyers, and those facing execution critical information about the lawfulness and reality of states’ execution procedures,” Wednesday’s report states.

Of the 32 states that have the death penalty, only eight have single-drug protocols for executions, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. Others, such as California, Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, North Carolina and Tennessee, have indicated their intention to move toward a system of one-drug executions. However experts say some of those states are under pressure to use chemical cocktails because of the difficulty in procuring the drugs necessary for single-dose executions.

The Constitution Project is considered a moderate thinktank that strives to bridge political divides. In order to achieve support from across the political spectrum, the panel shelved the question over whether the death penalty is right or wrong.

Its report highlights other weaknesses in the administration of the death penalty, including confusion over the law relating to death row inmates with intellectual disabilities, the poor standards in forensics used to obtain convictions and what the author’s say is a flawed clemency process.

“Without substantial revisions – not only to lethal injection, but across the board – the administration of capital punishment in America is unjust, disproportionate and very likely unconstitutional,” said committee member Mark Earley, a former Republican attorney general in Virginia. During his tenure, Virginia carried out 36 executions.

Other death penalty groups counter that while a single-dose execution may be safe and less likely to result in a botched execution, reforming the method of killing death row inmates misses the point. “At the end of the day, there is no right way to kill,” said Thenjiwe McHarris, a senior campaigner against the death penalty for Amnesty International.

“This report is asking for scientifically-reliable methods to minimise pain and suffering,” she added. “But the death penalty is cruel in and of itself; it violates the right to life. Giving someone a death warrant with the day and time that their life is going to be taken, taking them into a death chamber, administering a drug that takes their life – there is cruelty in that.”